This post is a practical summary of our experience pedalling across Argentina, from Buenos Aires to Junín de los Andes, from the 1st to the 29th of December 2016. The crossing of the Andes and the seven lakes route will be covered in a separate post.

The French readers among you can also check out our more descriptive travel journal posts in French: Route monotone et chaleur humaine, Une étape qui donne soif, and Je vois des montagnes!

Table of Contents

The route

To see the exact route we did, check out the map on the right side of this website.

Arriving in Argentina

We arrived in Argentina by boat from Carmelo, Uruguay. This is a nice boat trip across the Rio Uruguay, between small islands and through the picturesque channels of the Tigre Delta. The boat (operated by Cacciola Ferries) transports bicycles and arrives in Tigre, a suburb of Buenos Aires. We arrived on a Sunday, so Tigre was packed with people spending their Sunday there (there are numerous restaurants, an amusement park, shops, yachting, etc.). This kind of place is not our cup of tea, so we set off immediately in the direction of the centre of Buenos Aires. We followed mainly the Avenida del Libertador, which was easy riding as the streets were quite empty. Only in the very centre did we encounter more traffic.

Getting out of Buenos Aires

We didn’t feel like cycling in the traffic in the suburbs of Buenos Aires, so we considered the available public transport options. We had read about bicycle travellers taking the train towards Bahia Blanca in the past, which could give us a head start. But Argentina is cutting down train services very fast, and although the train to Bahia Blanca still existed, it didn’t have a luggage carriage anymore, so bicycles couldn’t be taken on board any longer. So, we took the next best option: taking a suburban train towards the south as far as possible, which was Cañuelas. The guy at the ticket counter suggested we take the train in the late morning, when it would be emptier.

Thus, one morning we cycled to Constitución train station on Buenos Aires’ cycle lanes (which are sometimes nice, sometimes very dangerous due to less-than-perfect intersections).

We bought a (really cheap) ticket (bikes don’t pay) and went towards the platform. It was packed. We had a hard time getting to the front of the train, where the bicycle compartment was situated. But once we managed to get there, we found space for our bikes, and as the train was quite modern it was easy to get inside with the bikes. On the whole route to Ezeiza (where we would have to change trains), the train got really, really packed. More people with bicycles came in, but as we took up quite a lot of space with our recumbents plus luggage, there was no more room in the “official” bike part. Anyway, most people didn’t seem to care too much.

The real experience started at Ezeiza, where we had to change trains. First, we had to get to the other platform, which was only accessible by taking stairs (first down, then up). The train station was very busy and we didn’t want to leave one of the bikes unattended, so we each grabbed a passer-by and asked them to help with the bikes (each of our loaded bikes weighs about 50 kg). It was quite a bit of an effort, but we managed to get to the platform. There, we discovered the next surprise: The train to Cañuelas was a very old model, with very steep steps to get up into the train. There was also a bit of confusion about where the luggage carriage (furgón) might be – in the end there was none. We had to take off our panniers and again ask some people for help to get everything into the train.

The train was only full at the beginning, then most people got off, we relaxed a bit and some people started talking to us about our trip and our bikes. The last challenge was getting off the train – our carriage stopped with the door right next to a wall, where we couldn’t get off with the bikes! So we had to cross to another carriage, take off the panniers again… We ended up on the main square in Cañuelas quite exhausted from this trip, eating our picnic, followed by a sweet in a nearby café. Had this train trip been worth it? The second part was extremely tiring and stressful. If we had to do it again, we would probably only go until Ezeiza, the road from there on looked reasonably quiet.

From Cañuelas we rode a while on road 205, there was quite a bit of traffic but there was a good side lane for us to ride on. We passed by the town centre of Lobos to get some cash (which was not as easy as it sounds, as we had to try all the banks until we found one that would accept our cards), and then continued to the Laguna de Lobos, where we stopped at the Club de Pesca campsite for two nights and a quiet day of rest, which we desperately needed after our stay in the big city of Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires State

Buenos Aires is quite a big state, and several roads cross it. We chose to take the ones that looked smaller on Google Maps, but retrospectively they’re probably all quite busy… more on that later. We crossed the state diagonally, first on route 205, then continuing on route 65 until Guaminí, where we would join route 60.

Leaving the Laguna de Lobos, we found the road quite frequented by trucks, but we had an asphalted side lane for riding until the town of Roque Pérez.

Until Saladillo there was no side lane anymore, but the road was reasonably quiet. In Saladillo we had our first experience camping at a petrol station – the big YPF station outside town on route 51, which we found by asking at a smaller YPF station in the town centre. It was actually a really good place to spend the night: there were tables and barbecues (of course, this is Argentina!), trees to give some shelter, showers, water, and a café open all night. Nobody seemed to find it strange that we asked to camp there – as we would experience over and over again, Argentinians have a very relaxed attitude about free camping.

After Saladillo, there’s a long stretch of road with more or less nothing until Bolívar. We knew that we wouldn’t be able to do it all in one day, so we were prepared to wild camp somewhere. We filled up our water at the last petrol station about 30 km from Saladillo, and cycled off on what would be our first of several “long stretches of nothing” in Argentina.

It was a flat, straight road with not much shade, with enormous fields on both sides, but almost no houses. Traffic was fluctuating, but there were quite a few trucks, and there was no side lane. We had our first experiences with reckless Argentinian drivers, which led us to acknowledge that we were the weaker ones in the game. From then on, we used our rearview mirrors extensively and learned how to quickly escape to the side of the road – into grass, gravel, sand, or whatever – when something was approaching from behind.

Towards the end of the day we had not much water left and were getting tired. By chance, we stopped at the roadside just when a truck was stopping, too. The driver had the best possible behaviour towards us cyclists – he offered us cold water before asking anything else. Once we were rehydrated, we had a nice chat with him (while drinking probably several litres of his water) and then continued a bit more relaxed. We still needed to find a place to sleep, which proved to be difficult. The fields were all fenced-off, many of them had been plowed, and there were very few trees or bushes to hide. There were also very few buildings next to the road, and we didn’t feel like taking a sandy road for several kilometres towards one of the villages… After 125 kilometres and close to exhaustion, we saw a minivan parked in front of a gate and went to investigate. The place was called Monte de los Recuerdos, a privately-owned sanctuary with a small chapel, a flowery garden and a freshwater well. We met the owner and caretaker a bit later, and he invited us to camp on the perfect lawn and help ourselves to water from the well. It was like heaven. It’s incredible how simple things – a bit of grass, fresh water, a welcoming gesture – can make you happy.

After this, it was only a short ride to Bolívar, where we decided to stay for the night because of a forecast of heavy rain and wind (which proved to be true). We had another experience of Argentinian generosity – we were spontaneously invited to spend the night for free at the sports centre’s dorm (the real story is actually a bit longer).

When we left the sports centre in the morning, we were warned about the truck traffic on the road to Guaminí. The warnings proved to be right. This stretch of road, which took us two days to cycle, was the second worst stretch in terms of traffic in Argentina (the worst was the stretch from Neuquén to Zapala). At some point, we wanted to get off the main road and try a small road marked on our map, but a guy stopped next to us and advised against it because it was very sandy – we trusted him, as he seemed to know the roads quite well and was a mountain biker. He promised that the road would get much calmer after Guaminí.

So, we continued on this road, staring all the time at our mirror, and escaping at regular intervals into the grass on the side of the road. The afternoon seemed a bit quieter, we saw many trucks stopped by the roadside, probably the drivers were doing siesta. We spent the night in Daireaux, where we could camp in the city park for free and take a shower at the sports centre. We also had the experience of getting interviewed for the local radio/TV-station – something that seems to happen at least once to almost all bicycle travellers in Argentina.

We continued on this busy road until Guaminí, where we spent the night in the official camp site, and then cycled another 15 kilometres on road 33, which was very busy with traffic, which we had expected because of what people had told us.

But as soon as we joined route 60, we were almost alone on the road. It felt great. We could actually cycle next to each other!

We arrived to Carhué on this road, where we ended up spending over a week in a holiday apartment (Miguel had to go back to Portugal for a couple of days for family reasons). Carhué is geared towards (mostly Argentinian) tourism and has several camp sites, many apartments for rent and a few hotels. It is located next to the salt lake Epecuén, and the main tourist attraction is an old village that has been flooded by the salt waters in the past. We found it a bit weird to market this abandoned village as the main tourist attraction of the region (it was basically a pile of rubble), but so be it… It was still a nice place to spend some time.

From Carhué we continued pedalling west on route 60, with a side wind which would sometimes push us a bit, sometimes slow us down.

After a week without cycling we decided to restart with a short day and stopped in Rivera, a small town, the last in Buenos Aires State. We arrived there in the early afternoon, at the beginning of siesta time. We managed anyway to find a café with Wifi and air conditioning to spend the afternoon, and found again a place to camp at the local sportsground. We took a shower at the nearby petrol station, and there was a sports bar where we had a nice cold beer before retreating to our tent. Unfortunately, there was a party going on all night at the sports hall so we only slept a couple of hours…

Crossing La Pampa

The last stretch of road in Bueno Aires State was a dusty affair, with roadworks going on and lots of sand next to the road. When we arrived at the sign for La Pampa, the road number changed from 60 to 18, and the asphalt got very nice and smooth.

For the time being, the landscape stayed much the same – very flat, huge yellow fields, not many trees. And it was quite hot and there was not a lot of shade. But the road was still reasonably quiet and we enjoyed the riding.

We stopped for a break in Macachín, one of the bigger towns on that route. It looked like a nice place and some friendly people came over to talk to us in the park, and a woman offered us cold water and some ice. But as it was still very early in the day we decided to continue a bit. We arrived in Doblas, the next town (or rather, village), again at siesta time, and everything was closed. Because of our previous experiences, we went straight to the sports ground, where we found some people preparing a roller-skating event. And again, we were very welcome to set up our tent there and take a shower. Fortunately, the roller-skating event was a kid’s event, and the music stopped before midnight. The only thing that kept us awake during the night was a big thunderstorm!

From Doblas, we decided to continue all the way west until Quehué and then take road 9 down to General Acha. It seemed much quieter than road 35, which branches off a bit before. After this long stretch of straight road, we were looking forward to turning southwards and maybe find a few curves in the road!

We stopped in Quéhué for our picnic lunch – the small town was completely deserted, even the petrol station was closed – and then arrived at the long-awaited turn towards the south. It was very hot and the landscape very monotonous, when we finally reached a small downhill – the first in days, or even weeks!

We spent the night in a hotel in General Acha, a typical stopover town for people travelling south – several hotels by the road (we chose one in the centre of town), supermarkets, bakeries, petrol stations, but otherwise not much interest.

It was here that the “real” crossing of La Pampa started. Most car drivers take road 20 to Veinticinco de Mayo (also called the desert road), and car drivers would tell us to avoid the more or less parallel road 152, which was supposedly in a bad state. The choice was very clear for us – we would take the “bad” road. We’d better navigate around a few potholes than having to get out of the way of the trucks and crazy cars. We knew that there was nothing between General Acha and Puelches, the next village, over 160 kilometres away. We were counting on getting water from drivers, and also on a hypothetical camp site in a small national park that we had made out on Google Maps. But as this was not a common road for cyclists to take, we couldn’t find much information.

So, we tried to get a reasonably early start and pedalled on route 152, which at the beginning was still surrounded by green fields and trees.

At the fork where road 143 splits off toward the “desert road”, we took a break. There was almost no shade, but in between the two roads there were some houses for road workers, surrounded by trees. Only one man seemed to be present, but he let us sit in the shade in front of one of the buildings to eat our picnic. He also filled our water bottles and we chatted a bit. He told us some anecdotes about other cyclists that had passed by.

The continuation of the road was nice. As we had been promised, it was very quiet. The fields had disappeared and replaced by wild grassland and small shrubs. We also saw a lot of butterflies. They came flying around our bikes as we passed by, as if they were playing with us! And the road was not that bad after all, at least not for cyclists.

In the afternoon, it got hotter and hotter, and we had less and less to drink. We got a little bit of water from a French family travelling in a motorhome. Soon it got very clear that we needed to reach the small national park (Lihué-Calel) and its (still hypothetical) camp site. It was a long way. After 123 kilometres, we reached the entrance to the national park, and there was a sign for the camp site, which was another 2 kilometres from the main road. We arrived there very tired and thirsty, we had no water left.

The camp site was there, it was for free and actually quite nicely situated, and it had tables, showers (the hot shower only worked on the women’s side), and even a Wifi network near the “museum” (but we didn’t try it). The only worry was that the park ranger told us that we couldn’t drink the water… he suggested we go to the small shop another 3 kilometres up the road to buy water! But he couldn’t tell us why the water should be dangerous to drink, and whether we cold filter or boil it, and then told us that “some people do drink it and they’re fine”. So, we decided to take the risk – afterwards we saw a sign in the toilets advising to boil the water before consuming it, so it couldn’t be that bad. We filtered a part and boiled what we needed for cooking and tea – and we survived.

The next day was again supposed to be very hot, up to 38°C, so we decided to pedal only the 35 km to Puelches. It was a small desert town without any interest, except for spending the night for those who have to. There were several hotels/motels, a petrol station with a basic café, and three small shops with a limited choice of food. We went shopping and spent the afternoon in our air-conditioned room writing, reading, doing laundry in the shower and cooking dinner on our fuel stove.

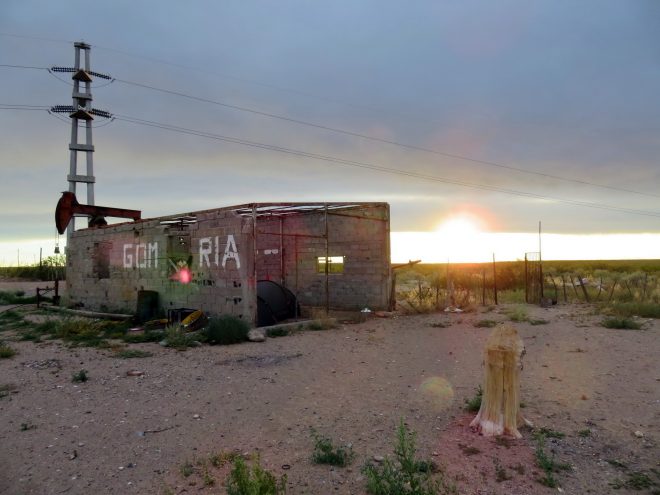

The weather forecast proved to be right, because the next day the temperatures were lower. We started at 7h30 after a typical Argentinian breakfast of coffee and a few pieces of dry cake (we stopped by the roadside later to have our breakfast of self-made muesli). It was another long stretch, 112 km until the next village of Casa de Piedra. This was the real, desert-like Pampa: dry, arid, no trees, no water, nothing. Monotonous, but in an interesting way. It also wasn’t as flat as before. Very slight hills started appearing, and although it wasn’t much, it was very nice. It’s actually very tiring to pedal on completely flat terrain, because there’s no variation of effort. We did have some headwind but not too much.

The road was empty most of the time, so we could take the kind of picture you can see on top of this page.

This time we had taken a bit more water – we can carry about 8 litres of water in our usual setup, and we had bought two additional 1,5 litre bottles in Puelches, just to be on the safe side. In the end, we didn’t drink that much as the weather was cooler and a bit overcast. The day ended up being easier than we expected, despite the length. Casa de Piedra seemed to be a village purpose-built for tourists, with a (free) camp site – basically a big park with toilets and showers (of which only one was working) – a hotel, a big petrol station with a café and wifi, and a small shop. And a lot of tiny mosquitoes! We set up our tent right next to the ambulance building, and soon a paramedic came out to say hello and to give us the wifi password!

It was another long ride to General Roca, and there were actually some hills to cross! They were gently announcing the end of the flat Pampa and the beginning of something hillier, which would end up in the Andes – but we still had several days to go until there.

We also crossed another state border. When arriving to Rio Negro State, we were surprised to find a control station, almost like entering another country. We discovered that it was prohibited to bring any type of fresh food into Rio Negro – fruit, cheese, meat. Fortunately, they were more interested in our bikes than our food, so they let us pass without checking.

In the late morning, we also passed a small roadside “café”, which we recognized by a hand-made wooden Coca-Cola sign outside, and where we bought a big bottle of fizzy drink and asked for some water. We reached General Roca in the late afternoon after crossing a last hill.

From there it was a short-ish ride (less than 50 km) to Neuquén, where we rented a studio for two nights to celebrate Christmas. To get there, we were told that the bigger route 22 was very busy and that there were lots of roadworks, so we chose the alternative route 65, which was busy but ok. We found ourselves surrounded by lots of fruit trees and green pastures, a welcome change to the dry Pampa! There was even a cycle path going into the centre of Neuquén (although it was not well signposted, we had to use the OsmAnd App).

Neuquén region – Towards the Andes

From Neuquén, we chose to take route 22 to Zapala, where we would take the famous Ruta 40. In the centre of Neuquén, route 22 is forbidden for bicycles, but there’s a small road running parallel to it, which was very quiet on Christmas day. A bit later, there was a “new” road right next to the main road, but as it was still not finished it was still closed to traffic. It was a great road to cycle on! There didn’t seem to be lots of roadworks going on, so this may well stay like this for months or even years.

We got a really bad headwind, so we stopped in Arroyito hoping to find a place to sit and eat. But the waterfront was not nice (and already full of people), the restaurant and hotel next to the petrol station were closed, so we ended up sitting all afternoon in a small restaurant by the road, talking to a Colombian truck driver. By the late afternoon, the wind had calmed down, and we decided to cycle a bit more and find a place to sleep next to the road. We had read that route 22 had heavy truck traffic (there are oil fields in the region and most of the oil seems to be transported by trucks). We hoped that on Christmas day it would be a bit quieter…

Well, there were not many trucks that evening, but still a lot of cars, and it was not nice. This was only the beginning of what would be the worst stretch of road on our trip through Argentina, and we would only be relieved in Zapala.

Fortunately, the days were long, so we pedalled on until about 19h30. We were eyeing the roadside for camping opportunities, but it seemed very difficult to find a protected spot – everything was fenced off and there were no trees. On top of a small hill, we reached a sanctuary to Saint Ceferino – it was clear that we would camp there. It was not as nice as the sanctuary where we had camped before, but there was a small, very simple bar. The friendly owners let us camp in their backyard, in a half-finished building. They had no running water, but we could buy drinks from their bar.

The stretch to Cutral Có was not nice at all – a lot of traffic, lots of trucks, a lot of stress, eyeing the mirror all the time and escaping onto the side of the road. When we arrived in Cutral Có in the early afternoon we were exhausted and fed up. Despite the siesta-time we found an open café with wifi and sat down to think over our options of the day – continue, camp, go to a hotel. That’s when we were approached by a friendly man, who wanted to organize free accommodation for us. Long story short, we ended up camping in his backyard and eating his wife’s delicious baked chicken for dinner, and going to bed much later than usually!

The last stretch to Zapala on route 22 was again a bit of the same, although the traffic calmed down once we got out of the oil fields. This stretch also held one of the nicest moments of our South American journey: We climbed a hill (called Subida de San Sebastián), and when we arrived to the top, we had a beautiful view of the snow-capped Andes for the first time. They were still very far, but they were there. A great moment and very difficult to describe in words!

By the way, and as a tip for other cyclists, on top of that hill there was another sanctuary (of San Sebastián), where we probably could have camped, too.

The rest of the way to Zapala was through a Pampa-like scenery, with the view of the Andes. It was beautiful and made us forget the traffic a bit.

We spent the night in Zapala, from where we finally joined the famous Ruta 40 which we took down to Junín de los Andes, where we wanted to take a few days off riding. Right from the start, leaving Zapala, it was like a huge breath of fresh air. The road was quiet, the views were nice, and the terrain hilly enough to make it interesting.

We had feared something similar to the Pampa – long stretches of nothing – so we carried lots of water. But this was much easier than the Pampa – we encountered several roadside stops selling drinks and basic food, and where we could fill up our water bottles. We could certainly have camped there, too. But we wanted to get to a place called Catán Lil, where we had spotted a river on the map and were hoping for a refreshing swim. So, we ended up doing yet another long day – 134 km, the longest of our trip. We arrived exhausted, just to realize that the river was all in private land and could not be accessed. But all ended well: we camped next to a small farmhouse, and the owner let us use his water tap.

The nice views continued until Junín. We spotted the Lanín volcano, and we had one of our best downhill rides ever, from a 1000-metre-plateau down to the village of La Rinconada.

In Junín, we stayed for a few days at the camp site Laura Vicuña (rather expensive but excellent hot showers!), where we planned our route crossing the Andes and celebrated New Year.

The drivers and the people

Nice things first – the people. Never have we felt so welcome as in Argentina (outside of the touristic Andes region, that is). Free camping was easy whenever we asked. People offered us hot showers, cold water and free accommodation. They were interested in our bikes and our trip, but would leave us in peace once we had set up our tent, so we could rest. They were very eager to give us information about the road – sometimes helpful, but often imprecise and sometimes even completely wrong. This was a recurring experience in South America: people would give us information that was way too optimistic – we’d like to think that they’re not consciously giving wrong information, but rather want to reassure and motivate us. Like that friendly guy at the hotel in Zapala, whom we asked about Ruta 40: He confirmed that there was much less traffic (which was true), but also assured us that it was “downhill all the way to Junín”… well, it wasn’t (but we knew that, we had studied the map). As a car driver, the downhills were probably all he ever remembered!

So, now comes the downside. When all these incredibly friendly people sit behind a wheel, they become some of the worst drivers we’ve ever encountered. We didn’t notice this at first, because there was a hard shoulder which gave us enough space. It was also alright on the quiet roads – cars and trucks would usually give us plenty of space when overtaking (although they would not slow down much). But it was an entirely different story on the busier roads: when two vehicles had to cross next to us, neither would slow down, they would just continue at their speed. On the rather narrow Argentinian roads (compared to the other countries where we’ve been), it was up to us cyclists to get out of the way, otherwise they would very likely just have run us over. This meant getting into gravel, sand, grass, whatever was there – most roads didn’t have an asphalted shoulder. It also meant that we continuously had to watch our mirrors (we probably only survived these roads thanks to the mirrors!) – those roads were one big stressful experience. The paradox is that Argentinians seem to be aware of their dangerous roads, and the places where someone died in an accident are marked with red paint on the road. Nevertheless, they don’t seem to consider changing their behaviour…

Another not-so-nice part were drivers stopping on the side of the road expressly to take close-up pictures of us. So yeah, we know that our recumbents attract lots of attention, that’s part of the game. We don’t mind people taking pictures discretely or from far away, or if they ask first, or come over for a chat showing that they’re interested in us. But in Argentina they would blatantly stand by the road and point their smartphones in our face from just a couple of metres’ distance. Preferably on an uphill, in the hot sun and at the end of a long day… without even saying hello or offering us some water, or demonstrating any other interest in us (other than as subjects for their facebook pictures). When we tried to explain why we thought this was rude, they just didn’t understand it.

Our host in Cutral Có, Juan, was very aware of this paradox between the nice, welcoming people and the reckless drivers (and I put the “smartphone photographers” in the same bag). He explained that the Argentinian as an individual is extremely friendly, but does not show respect for others when he has to function in a group or in society. We don’t know if other Argentinians would think the same, but at least it described our experience pretty well.

Basic necessities: Water, food and sleeping

Water

As long as there were villages, towns, or petrol stations, we had no problem getting water. We always drank the tap water and never had problems. We only used our water filter once in the camp site of Lihué Calel National Park. Only in the Pampa can it be difficult to get water, because there is literally nothing for hundreds of kilometres. But even the quietest roads we took had some traffic (at least one vehicle every 10 minutes), so asking for water (or food, or other help) would have been possible.

Food

Of course, we tried the famous Argentinian asado (although we must say that we preferred the ones we had in Uruguay…). You can get it at restaurants in bigger towns (or at someone’s home, I guess). The situation is a bit different in smaller towns and villages, where there are few restaurants, usually with limited choice. Villages always had at least one small shop, but the choice could be very limited (and they’re usually closed during siesta time). We found food relatively expensive, given the mediocre quality (Argentina has high taxes on foreign produce, and the local produce isn’t always of good quality). We also found many restaurants very mediocre, with very few exceptions. Breakfasts in hotels were also very limited, usually just coffee and some sort of cake, if you’re lucky you’ll get some bread. We therefore self-catered most of the time, eating pasta (ravioli and other fresh pasta is very common in Argentina) with whatever vegetable we were able to find (i.e. often not much) and always made our own breakfast of oats, nuts and dried fruit. It’s worth stocking up a bit at supermarkets when passing through bigger towns.

On the cooking side, it was very difficult to find fuel (white gas, or bencina) for the stove (we avoid using car gasoline because of the smell). Miguel found some in a Buenos Aires camping store, but it was quite sooty – we’re not sure whether this was actually white gas or something else. So, if you’re coming from Uruguay, this is something to bring! Otherwise, kerosene would have been easy to find for those who cook with that.

Money

Many ATM’s in Argentina didn’t accept our foreign cards. Just as in Uruguay, there were two networks – LINK and Banelco – but only Banelco worked with our cards. The withdrawal limit was very low – 2000 pesos (about 123 Euros) per withdrawal in December 2016 – but cost the equivalent of 6 USD every time. And as Argentina is not a cheap country, you end up withdrawing frequently and paying a lot for it.

Therefore, it is essential thing to bring cash in US Dollars. As the Argentinian peso devalues at high speed, people are more than happy to keep some of their money in dollars (who can blame them…). It’s very easy to exchange the dollars – but don’t go to the bank, it’s much too complicated. You can exchange in the streets in Buenos Aires. In smaller places, asking in certain shops is a good idea – such as electronics shops.

Just note that it’s very complicated to get US Dollars in Argentina, so take them from home – or from Uruguay, where you can get them out of the ATM.

Sleeping

The quality of hotels varied a lot, but we found them rather expensive for the quality. Camp sites were also on the expensive side, but most were well equipped and you can expect tables, barbecues, electricity, and hot showers included in the price. Free camping was easy outside the Andes region – good places to ask include petrol stations and sports centres (Argentinians love sports, and every village seems to have a sports ground). Many petrol stations have shower facilities (usually for a small price).

A note on spare parts

There are many bicycles in Argentina, mostly simple bicycles that people use to get around town. Almost every town will therefore have at least a basic bike shop/mechanic. But spare parts can be very difficult to get (this is also the case for camping gear) and is, above all, expensive. Argentinian customs charge a 50% import tax on foreign goods, even for items that are sent as free samples or gifts. We had new fuel filters sent to us by Katadyn (based in Switzerland), and they probably spent a fortune sending them by DHL. We got them all right in Buenos Aires, but Katadyn accepted to pay the import tax. We didn’t need any other spare parts while in Argentina, but we saw the offer in the bike shops which seemed very limited. Therefore, it’s a good idea to bring essential spare parts (or get them in Uruguay or Chile).

Dangers

The only real danger we were aware of in Argentina were the drivers. Other than that, the country seemed very safe. We took the usual precautions in Buenos Aires, but we didn’t feel less safe than in any other big city, such as Paris or London. Nobody considered it dangerous to camp next to a petrol station or in a park (outside bigger towns, obviously). There were lots of stray dogs around (especially in the camp sites – people use to feed them), but they were never aggressive (just keep an eye on your food).

Orientation

We bought a road map of Argentina, which was somewhat useful for planning the general direction in which we wanted to go, but it had quite a bit of information missing. As usually, we ended up using OsmAnd all the time. Once we were out of Buenos Aires and had decided on the road we would take, there weren’t many options anyway. Directions at intersections were usually signposted. OsmAnd was also useful for estimating distances, as distances on road signs were occasionally wrong. As said above, people’s advice can unfortunately not be trusted, unless you want to end up with underestimated distances and places that don’t exist…

The weather

We only got rain once in Buenos Aires State (and we were not even cycling). The weather was mostly sunny, sometimes hot and sometimes windy. It can be very hot in the Pampa, there’s no shade and water supply can be a problem. We got a bit of head wind when cycling through the Pampa, but only had to stop once because of the wind (when getting out of Neuquén). We used websites such as Windguru to predict wind and temperature, but it was not always very accurate on the wind.

So, how was it?

There are really two sides to this Argentina crossing. On one side, we are really happy to have crossed it all by bicycle. It was amazing to see the landscape change gradually, from the flat fields to the dry, desert-like Pampa to gently rolling hills, until arriving at the snowy mountains of the Andes. Riding for two days in a row through a semi-desert may be boring, but is also very interesting if you don’t mind being in the company of your own thoughts for a long while. The moment when we first spotted the Andes would never have been the same from a bus or car. And of course, it’s great that it’s so easy to camp everywhere and that people are so welcoming. We are happy to have seen the not-so-touristy side of Argentina, which we found quite different from the Andes region (especially busy regions such as the seven lakes).

But then there’s the other side. Some of the roads were so stressful because of the drivers, that we can say with certainty that we wouldn’t do it again. Spending a whole day with the fear in your stomach that you’re going to die under a truck is no fun.

Would we advise others to do it? Many of the roads we took were actually quiet and nice and we would definitely recommend crossing the Pampa by bicycle. An acceptable alternative could be to do the busier stretches by bus, or hitchhiking, and to cycle the quieter roads.

One thought on “So, how was it? – Two recumbents in Argentina”